|

||

In this section |

The Law Note: this page was written in 2006. I believe that the legal analysis was correct in relation to current account terms and conditions applicable at that time, However, in 2007, Britain's banks all rewrote their terms and conditions to try to get around the problems that they had with claims and with the impending test case. This means that the argument about common law penalties cannot be used in relation to these new terms; and with the ruling in October 2008, most of the old terms have also been declared by the judge to be OK in relation to common law penalties. Make sure that you read the page on the test case result and test case historical terms before using any of the arguments below in any claim. When a customer opens a bank account, he or she enters into a contract with the bank. That contract is governed by the usual laws of contract. These laws are derived from statutes enacted by Parliament; and by cases that have been determined in the courts over the years and have established precedents which are followed by judges in subsequent cases. When a bank makes charges to a customer for services provided, these form part of the terms of the contract, and, within reason, provided the customer has agreed to them, these charges can be at any level and the customer is legally obliged to pay these charges. When a bank customer exceeds their overdraft limit, they are breaking a term of their contract with the bank, i.e. that they should not do anything that causes their account to break the overdraft limit. This may be explicitly stated in the original agreement that the customer signed when opening the account, or it may be implicit in the way that the account is supposed to be operated. If the bank says that there is an “agreed overdraft limit” it is implicit that anything above this amount is “not agreed” and, therefore, the customer is breaking the contract by causing the limit to be breached. This breach may have been deliberate, where the customer knew that he or she would break the limit, or it may have been accidental where the customer did not realise that their action would break the limit. When the customer does this, the bank will either allow the transaction to go through and the customer’s negative balance will exceed the limit, or the bank will return the cheque or direct debit and refuse to honour it. In either case, the bank will generally impose a charge on the offending customer’s account. These charges are typically large, e.g. £20-30 for exceeding the limit then, possibly, a further charge of £3-10 per day that the account remains over the overdraft limit; or a fee of £25-35 for returning an unpaid cheque or direct debit. These charges are not charges for providing services under the contract; they are charges imposed because the customer has breached the terms of the contract. Under contract law, when either party to a contract breaks a term of the contract, the other party is entitled to recover damages for this breach. They could sue the other party in the courts to recover the damages. As this would not be very sensible for every minor breach of a contract, the law allows parties to a contract to agree in advance what damages would be payable if either party breaks a term of the contract. If the sum payable appears to the courts to be a genuine pre-estimate of the damages that are likely to be incurred, the courts will accept that this sum is what is called “liquidated damages” and the offending party will be obliged to pay this sum. However, if the sum specified in the contract is not a genuine pre-estimate of the loss that will be incurred but is excessive and is inserted in terrorem (to frighten the other party) the courts call this a “penalty” and the courts will not enforce it. These principles were first expressed in cases before the courts in the late 19th century and were explicitly laid down in a landmark case in 1915, Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co. Ltd. vs. New Garage and Motor Co. Ltd. The principles have been followed consistently ever since. Cases tend to reach the Court of Appeal or House of Lords every 10-15 years or so. Therefore, in the case of banks and their customers, the charges made by the bank because the customer has broken their overdraft limit should not exceed the damages that the bank has suffered because of the customer’s breach of contract. If the sum payable is excessive, it will become a penalty and will be unenforceable by the courts. The damages that the bank suffers if the customer’s overdraft limit has been exceeded are a) the customer now owes the bank more than he or she previously did, and, obviously the bank is entitled to recover this amount, but they will do so in due course anyway plus interest (unless the customer defaults all together); plus b) the costs incurred in notifying the customer of the incident. Does it really cost a bank £30 to send a computer generated, automated letter to the customer to notify them that the account has breached the overdraft limit? In many cases, the banks do not even send a letter but merely add the charges automatically at the end of the month. The damages that the bank suffers if they have to return a cheque or direct debit are merely the cost of sending the cheque back to the other bank or notifying them that the direct debit cannot be paid, plus the cost of notifying the offending customer. Does it really cost £30-35 to do these things when these processes are virtually all automated and generated by a computer, generally without any human intervention? It would seem to be very difficult for any bank to justify their charges as being liquidated damages. Note: the penalty clause arguments apply only to charges made because the customer has breached the contract such as by going over the overdraft limit. There is nothing to stop a bank having whatever charges that it likes (within reason) for providing a customer with services, e.g. for withdrawing cash from a cash machine, for providing a banker’s draft, for exchanging currency, for agreeing to an overdraft in the first place, for providing a mortgage etc. In addition to the common law principles that govern this issue, The Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999 provides further protection for consumers, i.e. in the case of bank accounts, a customer with a personal account, but not a business account. The UTCCR lays down criteria relating to terms in contracts between businesses and consumers particularly in relation to “Standard Terms and Conditions”. Terms in contracts can be held to be “unfair” if they breach these criteria, e.g. Schedule 2 “(e) requiring any consumer who fails to fulfil his obligation to pay a disproportionately high sum in compensation”. If a term is “unfair” it is not binding on the consumer. The consequence of the law is that if a customer has been charged penalty charges by his/her bank, he/she can sue for recovery of these charges because, despite the customer having signed to agree to the imposition of these charges, the terms of the contract were not binding on him/her. Why are these principles not more widely known amongst lawyers, bankers, and the media? How could banks possibly get away with acting unlawfully for years? The proposition that banks have been deliberately breaking the law for years and plundering their customers’ accounts and not being stopped from doing so would seem, at first sight, to be incredible. The problem that lawyers have on this matter is that, if asked for a legal opinion on an issue, they will look for precedents in higher court cases. There are strong precedents on penalty charges, but not relating to bank charges. No case has ever gone to a higher court on the issue of bank charges (although Bridge vs. Campbell Discount Co. Ltd. did relate to an H.P. agreement) and so lawyers, being naturally conservative on these matters, will always say “well it could be argued that …, or it could be argued so and so etc.” Furthermore, there is no reasonable hope of a solicitor or barrister ever being paid to represent a client to recover bank penalty charges. And if banks consistently pay up when sued, no case will ever get to a higher court to set a precedent. Note: the test case has now happened and the result is analysed on the page test case result. |

|||

|

||||

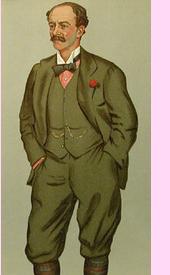

Lord Dunedin who made the ruling on penalty charges in Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co. Ltd. vs. New Garage and Motor Co. (1915). His ruling has been consistently followed for nearly 100 years. He probably never imagined what an impact his ruling would have for potentially millions of people 70 years after his death. If you win back from your bank a large sum of money, say a little prayer for him. It was Dunedin what won it! |

||||

Published and promoted by Bob Egerton, TR2 4RS |

||